After an hour of lying there, Doug got up. He did this slowly, careful with the bedsprings, as if I’d been sleeping. I watched him pull his shorts on, then the jeans and dress shirt he’d worn earlier. There was a fan going in the window, but I was still sweating under that single layer of bed sheet, the comforter thrown to the foot of the bed. The idea of putting on clothes made me feel hotter.

“You going out?” I asked.

Doug didn’t look at me. It was dark, but the lights had been out long enough for our eyes to adjust. “Can’t sleep.” He was whispering. He was bent over himself putting on socks. “Just gonna take a short walk.”

“It’s so hot,” I said. I should have asked if Doug would prefer that I leave, if it was because I’d lied about my age on my profile—not by much, enough for it to be a thing, enough for it to make dinner and drinks a little too quiet, though maybe that had nothing to do with my age—but the sheets were bunching around my feet now and my face was wet. It was all I could think to say.

“I’ll be back,” Doug said. “Just can’t sleep.” He went to the door, which wasn’t a door but rather a curtain he’d hung to separate the room from the rest of the apartment. When we first arrived, I’d wondered what this room might originally have been intended for, imagining a small nursery, all green plants dangling and reaching and breathing, and sunlight, more than that little window would allow. All that moist air.

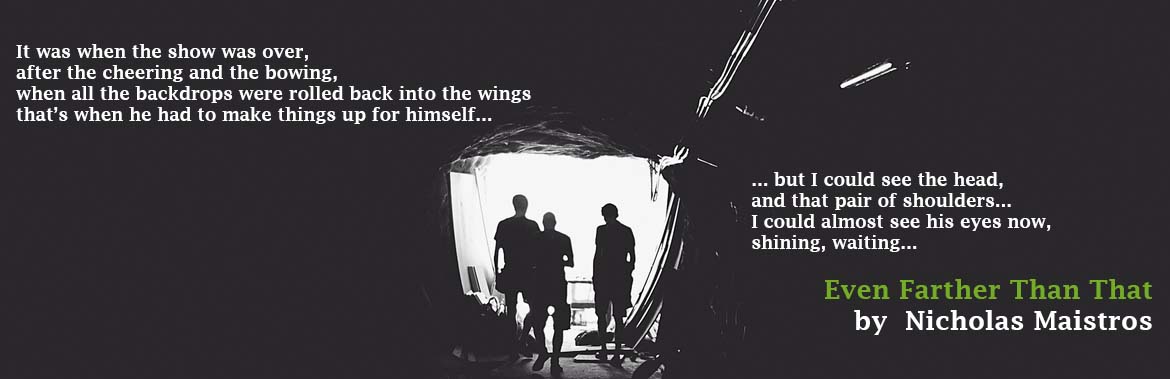

I had liked the curtain, along with the mix of tastes in the living room furniture, that sense of different young people colliding, trying to make their Wrigleyville apartment work. I had also liked passing the stadium in the car on my way here. The lights had been up, though there was still daylight, moving into dusk, and I’d thought about all those baseball fans watching the game. Their cheers. That was before dinner and drinks. Doug stopped at the curtain. There was a strip of lamplight on him. “If you’re hungry,” he said, “there’s food in the fridge. Just be sure my name’s on it. Malachi’s uptight about that.” He pulled the curtain and slid through. I waited to hear a conversation with Malachi, or someone else who might be restlessly wandering these rooms, what Doug might have to say about me and the tone he said it with. But there was only the sound of the fan now. I listened for the game that might still be happening a few blocks away.

Doug had been kind about things. When I had stopped, moved his hand off of me, said sorry and rested my head on his shoulder, he’d let it all go, even stroked my hair for a while. I imagined Doug outside now, looking up at this window from behind a bush across the street, waiting for me to leave so he could sneak back up and sleep alone. Things hadn’t gone as expected, and I knew it. But I didn’t know what I’d do if I left. Home was three and a quarter hours away, and right then, it felt even farther than that.

I switched on a lamp and took a book from the side table, a play I hadn’t heard of. All the lines of someone named Lorenzo were highlighted. I read only those lines and pictured Doug reading them with an Italian accent. “The part of a lifetime,” he’d said at dinner. “Tomorrow morning. Ten a.m. So don’t you keep me up too late.” I was supposed to react to that, to say something that would make up for our age difference or even take advantage of it, if that difference mattered at all, something like, Let’s just see what happens, with a wink, a touch, some seedy and fabulous gesture. That’s what I was supposed to do.

I chose a shirt from Doug’s closet thinking, justifying, that mine was all balled up and wrinkled on the floor. I chose a shirt that I guessed was Doug’s favorite, a bright yellow tee discolored at the pits, a tiny hole worn into the neckline. This was the shirt he’d worn in his profile pic, wasn’t it? His confident yellow skin that felt more like Doug than Doug—a desirable, youthful, two-dimensional Doug with all the potential depth and complexity that a profile pic could promise.

It was small and stuck to me. I didn’t feel like Doug, but I didn’t feel quite myself either.

When I went to the curtain, the sound of Malachi’s voice stopped me. Malachi had been there when we got in from dinner and drinks—this skinny African American boy with painted toenails curled up in an armchair. For a second I thought this was the babysitter and there were little ones asleep down the hall. He had that severe look of teenage resentment, bored and annoyed, here and not wanting to be. He was watching TV.

“That’s Malachi,” Doug had said, and he moved to the curtain. Malachi looked up from his show to smile at me, as though he might as well, a prepared smile from a file folder of different smiles. His eyes were absurdly large for his little bony face, and expectant. I felt I had to do something to amuse him, but he said “hi” and looked back at the television. The movement of his head was so slight, I could have sworn he hadn’t moved at all.

I listened to him now through the curtain.

“I’m just saying, sometimes you…well, babe, sometimes you start into things.” He was quiet, as though he thought I was asleep, or doing things with Doug. Or maybe he couldn’t be brought to speak any louder, didn’t have it in him. “You start into things you know nothing about, and what am I supposed to do?” He was on the phone. “Mm. So I’m supposed to sit there and let you go on—yes, that sounds right. On and on, making shit up while everyone laughs at you and thinks you’re…” He sounded disinterested, like he was doing something more important—a crossword, his toenails. “Okay then, don’t come over.” He felt nothing. “Right, I’m an asshole. I know. Sleep well.”

And then silence. I thought to slink back into bed, shut off the light—with Doug gone, this was Malachi’s space. But it was too hot, and I was hungry and needed something cold from the fridge.

No, that wasn’t it. It’s what I told myself, but that wasn’t it.

I pulled back the curtain and saw him standing next to the bay window, his arms flat against his sides. He was short—the tiny neighborhood babysitter, five dollars an hour, no talking to boys—but he seemed to make up for it with his posture. So straight and poised I wouldn’t have been surprised to find someone else in the room, a photographer focusing his lens, or an artist with a color palette, telling him not to move a muscle. I looked down to see the cell phone in his hand, his grip on it loose. It was hanging there, like it might drop any second. When I looked up, Malachi was looking back at me. Those large eyes, blank yet concentrated, the way a person reconsiders something said too hastily, the way he looked at anything.

“I didn’t mean to interrupt,” I said.

“Nothing to interrupt,” he said. He brought his hand up to play with his necklace.

I pushed the curtain fully open and stepped out. “I was just going to get something from the fridge,” I said. I found that I was whispering.

“Where’s Doug?” he asked. He was not whispering.

“Went for a walk.” Malachi didn’t respond to this. He was still analyzing me, still standing so straight. “Does he do that a lot? Go for walks?”

“Doug’s an asshole,” he said.

I laughed. Malachi’s face changed, and I thought he might laugh too, but then he threw his phone across the room. My shoulders leapt up. I thought it was at the sound of the thing hitting a wall and the battery popping out, the parts of the phone clattering to the hardwood floor, but really it was the movement that did it. Malachi in motion. How he spun on his feet and how his knobby elbow cut the sticky apartment air. The flip of his wrist and his splayed fingers as the phone left him.

Malachi’s arms went back to his sides. He didn’t seem to be breathing. It was as though he was only considering now, the phone already busted and dead on the floor, whether or not to throw it. Then he said, “You want a drink?” He went into the kitchen. “I’ve got this scotch.”

“Okay,” I said. I looked at the mark in the drywall and realized I was smiling, and that I felt suddenly cool, a chill. I shivered.

He came back and handed me a glass. “Don’t expect much,” he said. I was still standing by Doug’s room and he leaned against the back of the loveseat. We took a sip together and I felt warm again.

“You in school?” I asked, not sure why I asked it. There was a tickle in my throat and it was hard to say. He was watching me. The scotch didn’t seem to burn him at all.

“How old do you think I am?” he said. He almost had a smile now.

I shook my head, apologizing. “I’m bad with ages,” I said. I would’ve guessed seventeen, but I knew that must not be right.

“Thirty-seven,” he said.

“Thirty-seven?”

“Not me, sugar. You. You are thirty-seven. Wait, thirty-nine.”

For a moment, I thought, Am I really? Am I thirty-nine? “Wow. You’re good.” […]

Subscribers can read the full version by logging in. |

____________________________________

Nicholas Maistros holds an MFA in fiction from Colorado State University. His stories and essays have appeared or are forthcoming in Bellingham Review, Nimrod, The Literary Review, Sycamore Review, and Witness. Nicholas also writes book reviews for Colorado Review and is completing his first novel.