Read More: A brief Q&A with Wren Burton

Ways I’ve told the story:

In poorly veiled and poorly executed fiction, in college

In hypotheticals, to a cafeteria table of girls cooler than me my senior year of high school (“Are they both cute?”)

As a confession of cheating, to my girlfriend at the time

As an offhand reference related to sex work, in a Women’s Studies class

Not the way my shrink told it, as years of molestation and nexus of PTSD

Never as a rape — for, after all, hadn’t she saved me from that precise thing?

That never happened

Never as fun

Never as something I’d wanted

Always, as something I must’ve wanted

To everyone: as something I’d deserved

![]()

When I turned 16, I got a job at a music store owned by my mother’s friend and former yoga student. It was a family business: two sisters had inherited it from their father, and ran it with their husbands along with one sister’s daughter and her fiancé, not yet her husband. There were three unrelated guys who worked on the guitar side of the store; there were two other girls beside me, and we were called The Counter Chicks (it was the 90s). We did everything on the side of the store that wasn’t guitars or amps: registers, pricing reeds, stringing and tuning violins, alphabetizing sheet music, inventorying, dusting, polishing, processing rental contracts for three-quarter size cellos and flutes with curved headjoints that creaked out to a carousel of public school students and returned at the end of the year either a bit more cracked and scratched, or still retaining the bright glow of the rosin I’d rubbed in back in September, the case hinges stiff with unuse. I had my first cigarettes on the loading dock out back.

![]()

How I’ve explained how it happened:

I didn’t have a driver’s license because I’d chosen to be in a musical that rehearsed at the same time driver’s ed ran, and my parents wouldn’t let me take the test without having taken the class.

The air in my home was dried to brittle dangerousness, like an ancient well-cover. I was my parents’ only child and I had become a disappointment.

I had always been gay but didn’t put together the word and the feelings until 6th grade. Then, I’d promised myself I’d wait until college to come out. It seemed safer that way. This is part of the story, too, the way a bayleaf is part of soup.

My freshman year of high school, I fell in love, and an ex-boyfriend’s mom outed me to my parents. It ruined things for my parents, or at least my mother, meaning I’d ruined my mother, meaning I threw up all the time and nothing was okay.

I was a bad good girl. My parents didn’t kick me out — everyone would have known. I was a bad good girl who knew all about personal responsibility and God and sin and ethical morality and penance. I went to Catholic school and anything on paper came easily.

![]()

Things I remember liking about my body:

My breasts

My very long hair

My lips

My height

My long legs

My voice

My hands

Things I remember hating about my body:

My breasts

My skin

My eyebrows

My thighs

My weight

Ingesting food

Having a body in general

I spent a lot of time fingering the bruise of the experience I’m talking about, trying to test out its nebulous borders, identify how deep it went versus how deep it should go or I thought it went, wondering how much of it — not all, surely? — was self-inflicted. It’s just a body. I had a mantra: nothing happened, nothing happened, that didn’t happen.

Even my language was suspect; the world “that” needs a reference, a specific referent, heading back to the idea of nothingness waving its crossed Ts at itself, the events, my body.

It is surprisingly easy to hide and be hidden. Once my mother asked me without a full sentence — “He isn’t…? Be careful.” I brushed it off, I laughed, I went outside and I got in the car. Isn’t that how you define a choice?

![]()

You should have names, even though I’m making them up. Willa was Martha’s niece, and Chris was the man she lived with and who would be her husband within a year. She was just three years older than me but seemed more; Chris, six years older.

Is that right? Is it possible? Was Willa really in college, the age of my students now, the students who could be my children? I can’t imagine being afraid of them. Ten, fifteen years apart for adults is nothing. Am I really still thinking about this?

I think Willa was doing student teaching — she was so good with the six-year-olds. Do I remember that? Chris hadn’t gone to college. He owned real estate and a truck and a boat.

The story I’m trying to tell you is about Willa and Chris and me, and you already know that, I’m nearly sure. Nearly sure is the way I tell this story.

After college, I worked for a company that produced dictionaries, thesauruses, and glossaries. My first project was on antonymy: only some words are true antonyms. Others live only in the vicinity of oppositeness. There are no true antonyms for the word “rape.” The synonyms are sexual assault, ravishment, violation. The antonym for ravishment is “noncrime.” The antonym for violation is “noncrime.”

![]()

This is not the story of a noncrime; or, it is the story of a noncrime.

The first recorded use of the word “noncrime” was in 1909, along with “libido” and “lie detector.”

The antonym for “molest” is “be careful” or “protect.”

I did not write that entry unless I did and don’t remember.

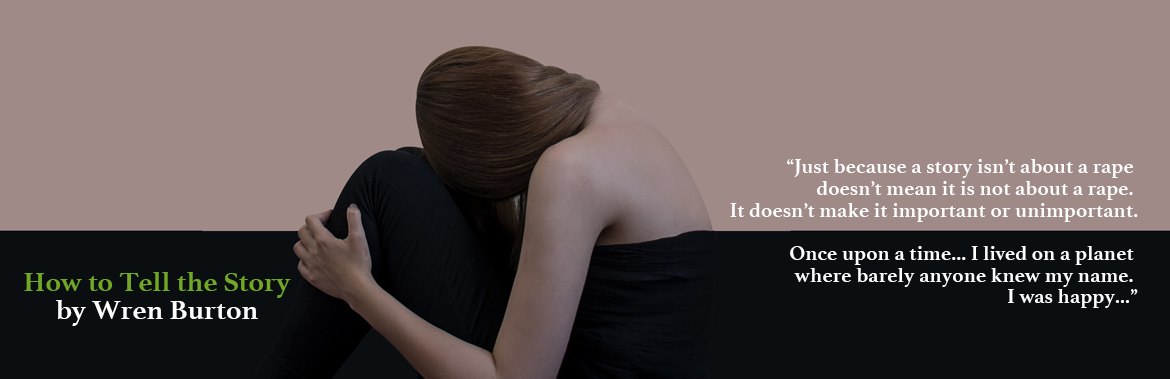

When I was in grad school, I said to a woman across the table from me, a high school English teacher from Queens whom I’d later mess around with on a beanbag chair in a reading room of the Sarah Lawrence library, “Just because it’s about rape doesn’t mean it’s a good poem.”

Just because a story isn’t about a rape doesn’t mean it is not about a rape. It doesn’t make it important or unimportant.

Things the Bible tells us aren’t important:

Worrying

Saving money

Doing the dishes when Jesus comes over for dinner

Trying to eradicate poverty

Things the Bible tells us are important:

Loving your neighbor

Not repaying an evil with evil

Forgiveness

Not leaning on your own understanding

I had a hard time making it through sleepovers until I was 11. I had a large vocabulary of archaic British words, but not a large vocabulary of emotion words. Anything awful I felt was called “guilt.” Everything awful I felt was called “my fault.”

As I look at my 40th year, the most recent words people have used to describe me (within my earshot, at least, and I am aware that the list of words out of my earshot must be very different) are fierce, funny, and crazy. When I was fifteen, it was weird and fuckable.

I did think Willa was beautiful.

Her hair curled perfectly, fat round ringlets in a bob, the color that I’d never understood calling dirty blonde. Her eyes were so large and full-lashed, her lips so turned-out in a small face that I do understand calling heart-shaped.

She had square tipped acrylic nails, not too long. She smelled like the kind of girl-products that I’d never gotten near. Some secret smell. She thought I was

I’ll never know what she thought I was because I can’t remember and I won’t find her to ask.

Anyway, you can see how this was my fault. I had thought she was beautiful. And who did I tell?

Look ahead: in my 30s I had this long beautiful descent into alcohol. Bliss! For years, drunk at the end of every day! And no one noticed! I am that good.

I don’t want to be dramatic. The age of consent in Pennsylvania at the time was 16.

(Nothing happened nothing happened that didn’t happen)

Then I quit and of course no one noticed except maybe that I was less fun at parties because of course everything was as it was before and I was still taking care of everything I had always been taking care of. I’m that good!

Look, all this has nothing to do with anything at all, except why am I bringing it up. I’m not trying to give you a throughline. Those are too simple, and they’re always lies that suit another lie. That’s why we call them plots.

Pick the option easier for you to believe:

- It was the husband’s fault

- It was the wife’s fault

- It was the girl’s fault

- It was the fault of the heteronormative patriarchy/the Catholic school skirt

- 1 and 2 and 4

- All/None of the above

Things that Chris told me:

He’d hidden cameras in their house and had footage of me doing everything

He’d put a stroke tracker on the computer at work, and he’d captured my email password and all my contacts

He knew I liked it

He’d give me fifty dollars, a hundred dollars, a vibrator, vodka, wine, weed

He’d tell everyone

He wasn’t too drunk or too high to drive

I couldn’t get away

He could do everything he wanted, and he’d tell everyone about me

You know you want it you know you want it you know you want it

Willa and Chris were my managers at work. Willa and Chris were married. Willa and Chris had a hot tub. This is what they were like: once, they went on a cruise, and Willa won best bikini body, but Chris thought she should get implants because her breasts were actually quite small and her bikini top had been padded.

A thing I felt guilty for: not enjoying it. Couldn’t a good bad girl have had a good time? A different story.

What if it was a different story? Let’s try it:

Once upon a time there was a young beautiful couple and they met a younger girl and the three of them were happy, the end.

Once upon a time there was a girl as free with her body as she was with her breath and

No.

Once upon a time there was a girl and a girl and a man and there are several videos on this topic, please use keyword “menage a trois”

Once upon a time there was a workplace sexual harassment video that hadn’t yet been made but if it had been made it is likely that it would cover issues such as waiting naked in the storeroom while you have someone else send that high school girl back there

Once upon a time there was a girl who got used to a lot of things and also she was drunk

It went on for two years.

We get used to so much in the course of two years. We have to. How else can we live?

I want you to know everything got better.

Too many sentences sound like a form in a doctor’s office. I hate going to the doctor. How do I tell the story? Why tell such a tiny part of my whole big life? […]

Subscribers can read the full version by logging in. |

___________________________________