Read More: A brief Q&A with Ryane Nicole Granados

Dear Sonshine,

That’s what I call you because the mere sight of your go big or go home smile is like the sun filtering through our shutters on a bright California day. It’s the summer before your 13th birthday but for months now you’ve been reiterating that you’re taller than me, that you can almost fit in your father’s shoes, that your dreams are ever-changing: soccer player, drummer, paramedic. You are just as strong-willed as you were as a toddler, but to my delight your personality has also emerged as outgoing and kind. You are compassionate to strangers, concerned about world issues, and you are constantly, unabashedly questioning. It is usually in these moments of inquiry where my enchantment with you turns to frustration and fear. You see son, I have lived in this Black skin longer than you have. I have learned to walk a fine line between approachable and articulate, between joy and rage. I know that the difference between coming home alive or becoming a hashtag might be the stifling of my understandable need to question someone’s unjust begrudging of my humanity. So your father and I usually exchange a glance and maybe a sigh and in the small window before you disappear into your video games with friends, we try to explain to you the terrifying duality of being Black and being perceived as an adult in America.

I have never been in a rush for you to grow up. I miss the days where when your cheeks ballooned like they were filled with cotton candy and your tiny hands still had that soft pudge of baby fat and unspecified preschool stickiness. I cringed in your early elementary years when well-meaning people would comment on how tall you were for your age or enthusiastic barbers would call you “little man” as you walked self-possessed into the barbershop. I wanted to stop time when you hit the double digits because as long as you were animated and adorable by society’s standards you were protected, or so I thought, from the perils of racism and police brutality.

But then you turned 11. Seemingly overnight you had a huge growth spurt met with painful spasms in your legs. Your father would spend the evenings massaging your muscles and your physical pain mirrored my maternal worry that growing up could actually hurt you. This reality was magnified one afternoon when I was waiting for you outside of school. We’ve always taught you to never run when crossing the street. You know to only begin walking when the little man is blinking and most importantly you know Dad, Nana, or I will always be waiting on the other side to greet you. On this particular day a police officer pulled into the crosswalk and swerved his squad car beside you yelling on his loudspeaker for you to hurry up and get across. The little white man was still blinking. At the realization that the officer’s car was coming right in your direction, you froze in fear like your legs were stuck in a spasm. I could see from a distance the furrow in your brow right above the scar from when you fell and hit your head on the coffee table at two. That furrow is your questioning wrinkle: should you run, should you walk, should you put your hands up, what should you do? At that point the police officer flashed his lights at you. At 11 years old you were admittedly the height of a 13-year-old, but you were still a child. You were still my child. I hopped out of my running car leaving your little brother strapped in his car seat and ran into the crosswalk screaming, “He is only 11 years old.” Other parents, white parents, having known you since kindergarten, started screaming at the officer too. I secretly hoped their whiteness would be a shield for you. I wondered if we should yell out a catalogue of your supposed worthiness for you to be treated with human decency: that you have straight A’s, play drums in a kid’s rock band, that you’re training in taekwondo when not participating in youth church. I lunged in front of the police car to protect you the same way I promised during the emergency C-section of your delivery that I would die for you. As the other parents were demanding the officer’s badge number, he screeched his car around us all speeding through our once safeguarded school zone. Before that day, you professed you wanted to be a police officer when you grew up. You now express you want to be a paramedic because you want to help people.

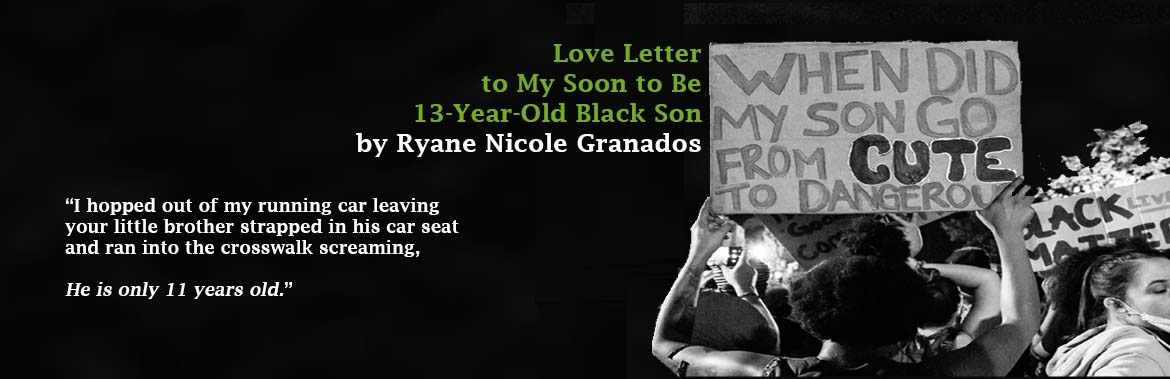

In a few short months you will be the actual age that you appeared to be when you were 11. You no longer talk about that incident outside of the school and you’ve already begun to develop a hardened jawline where those candy-coated cheeks used to be. But one trait that remains is your questioning. So I can’t wear my black hoodie because of what happened to Trayvon? I can’t go jogging anymore because of what they did to Ahmaud? Every year of your young life, names have been added to a running list of Black bodies. They are real-life characters in a cautionary tale. We speak of them like family. They are play cousins or distant uncles who we mourn and grieve and before the sorrow extinguishes, there’s another name added to the list.

When I was in middle school, around the same age as you are now, the image of Rodney King being struck repeatedly by police played on loop on the TV and still today in my tarnished dreams. I was naïve enough then to think that video proof was the same as irrefutable truth, but the older men at the corner store knew better. I would overhear them saying, “They’re gonna get off” and I thought to myself such foolish old men. They knew nothing about hope and technology and the power of the tape. With the certainty that only a preteen could possess, I dismissed their comments drowning them out with music from my Sony Walkman. And now I’m the foolish one and you’re in middle school and your fingertips scroll through countless images of hope lost and technology unheeded, your cell phone housing tragedy on tape. I repossess it trying to censor you from its content. This isn’t a Hollywood movie or a video game. This is a real-life public lynching where a knee is dug into George Floyd’s neck for 8 minutes and 46 seconds, causing his soul to seep out of his body as he calls out for his dead mother. I beg you to never watch it. I implore you to take a walk with me instead. We make our way to the hiking trails at the top of our street and below I can see the remnants of dilapidated buildings never rebuilt from the fires that blazed in Rodney King’s name. It’s a dizzying form of déjà vu. Then you tell me you want to protest.

For a moment I forget that we aren’t just dealing with the pandemic of racism. There is a disease, a novel coronavirus that is killing people indiscriminately. You also have a medical procedure coming up. It’s my job to keep you safe. Yet once again I feel the expressiveness I always wanted to encourage in my children becoming suppressed under the weight of a world that demands you be silent. I tell you it isn’t safe for you to protest. You can’t be around that many people so close to your surgery. I can see your frown tighten under your mask as your brow gives off its familiar furrow. You don’t say anything to me as we walk home. In a sulk, you pop in your AirPods.

As we juggle two pandemics at once, I get to see you finding your own voice amid a new generation of burgeoning activists. I still don’t let you join a protest march and for that I feel like a fraud disappointing her comrades of 1992. Instead, you decide to make your final project for your art class a tribute piece to Black lives. You marry your love of drumming and photography by taking the first drum you ever owned and repurposing it with pictures of unarmed Black men, women, and children killed because of unbridled hate. You complain that there are so many faces you can’t fit them all on your drum. You mention that “a drum is like a heartbeat, so every time you play you will be playing for those whose hearts no longer beat.” This is what it means to turn 13 while being Black in America.

Your drum looks like an oversized birthday cake and I can’t help but feel the heartache of Tamir and Michael and Breonna’s mothers who no longer get to see their children add candles to their cakes. I should be celebrating you getting older instead of begrudging it. You deserve to grow and evolve; to be happy with your friends and snarky with your parents, to make all the typical coming-of-age mistakes that any teenager might make without the added burden of your skin being weaponized against you. You are right to question why I am having the same conversations with you that Nana had with me, that your Great Granny had with Nana.

A year after you were born, the United States elected its first ever African-American president. For the bulk of your formative years, this was the only president you ever knew. Your Dad and I still chuckle at how you commented during the election season of your 9th birthday that you didn’t know so many white people were running for president too. You had a lifetime to learn that you were born under a rare banner of historical significance. Your innocence felt sacred and magical; something too sweet to correct too soon. But you are wising up now as fast as you are rising up, and I see hope in you. I see your smile like welcomed sunshine burning off the haze of June gloom. I feel you resting your long arm on my shoulder, towering over me, casting shadows in the breeze. I imagine our chorus of laughter as we sing Happy Birthday loud and off-key. Stevie Wonder’s version of course. I see your destiny. And in these last few months before you turn the long-awaited 13, I see that watching you age has been the ultimate gift to me. In return, I offer you these words of love simply stated to my soon-to-be teenage Black son,

“Now and forevermore, in a world that needs your light, you matter!”

Love, Mom

Subscribers can read all our publications by logging in. |

__________________________________

Ryane Nicole Granados is a Los Angeles native and she earned her MFA in Creative Writing from Antioch University, Los Angeles. Her work has been featured in various publications including Pangyrus, The Manifest-Station, Forth Magazine, The Nervous Breakdown, The Atticus Review and LA Parent Magazine. Her storytelling has also been nominated for a Pushcart Prize and showcased in KPCC’s live series Unheard LA.

“Love Letter to My Soon to Be 13-Year-Old Black Son” Originally appeared in Pangyrus Magazine.

Read More: A brief Q&A with Ryane Nicole Granados